“I already know a thing or two. I know it’s not clothes that make women beautiful or otherwise, nor beauty care, nor expensive creams, nor the distinction or costliness of their finery. I know the problem lies elsewhere. I don’t know where. I only know it isn’t where women think. I look at the women in the streets of Saigon, and up-country. Some of them are very beautiful, very white, they take enormous care of their beauty here, especially up-country. They don’t do anything, just save themselves up, save themselves up for Europe, for lovers, holidays in Italy, the long six-months’ leaves every three years, when at last they’ll be able to talk about what it’s like here, this peculiar colonial existence, the marvellous domestic service provided by the houseboys, the vegetation, the dances, the white villas, big enough to get lost in, occupied by officials in distant outposts. They wait, these women. They dress just for the sake of dressing. They look at themselves. In the shade of their villas, they look at themselves for later on, they dream of romance, they already have huge wardrobes full of more dresses than they know what to do with, added together one by one like time, like the long days of waiting. Some of them go mad. Some are deserted for a young maid who keeps her mouth shut. Ditched. You can hear the word hit them, hear the sound of the blow. Some kill themselves.”

— “The Lover”, Marguerite Duras

Many women, regardless of their cultural, political or ideological background, invest much of their energy into “preserving” themselves. The neurosis about wrinkles or body’s changes during the monthly cycle or during/after pregnancy, about gaining weight, about getting dark spots or a darker shade of skin (which your culture may consider as something “bad”) from enjoying the Sun a little too much… We could probably create an infinite list of neuroses, concerns and worries that occupy many women’s minds; however, what they all narrow down to is the perpetual pursuit of “perfection” or “purity”.

[This is not an articles that tells you that you should not care about your appearance or beauty — anyone reading Volupta knows that Volupta encourages pursuit of beautification and glamour. Still, devotion towards Beauty and perfection neuroses are different things I wrote of it more here]

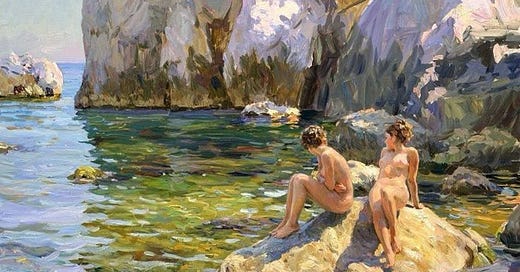

Our culture generally celebrates the Maiden-like qualities in women. Undoubtedly beautiful, inspiring and moving, and with her own mysteries, when the Maiden and her lightness, her blessed not-knowing and her perpetual potential are the only ideals, the other aspects within a woman that yearn to be seen and actualised may not find their mirror.

Even if a woman physically has children and becomes a mother, very often, psychological or inner transformation may have not occurred — untransformed Maiden then uses the children to to sustain her fantasy of a “perfect family” and her identity as a “perfect mother”. She still dwells in the intangible and in the escapist fantasy and on the level of being, nothing has changed.

The “imperfection” of the physical life, of blood and flesh, is something she cannot face and something that she actively seeks to avoid. The lionisation of the Maiden creates consciousness that hovers above the earth rather than sinking roots into the dark, moist soil of embodied experience. The body itself becomes the enemy in this paradigm - its changes, its hungers, its messy desires all threatening the crystalline perfection of the idealised feminine.

While cultural framework can be used to understand the collective experience, the individual is still an agent. Many women, even in their own individuality, prefer to remain in the perfection of the potential rather than move towards the actualisation. She, consciously or unconsciously, believes that her worth diminishes with every experience, every year, every wrinkle. And God forbid if she has wounds or scars. This creates a psychological incentive to remain symbolically untouched and unaffected by life and experiences even when physically participating in life.

The perfection of potential creates neuroses, yet its stagnancy is also deeply comfortable and lulling. In potential, a woman can postpone confronting her own desires when they conflict with others' expectations. She can avoid the responsibility of wielding power. She can avoid making hard choices by claiming she doesn't yet know her mind. She can remain in the potentiality of becoming rather than the responsibility of being. She can perpetually dream of life, of romance without ever being affected by any of it.

Actualising yourself and becoming embodied brings change to this — actualisation requires full presence and accountability. The embodied power demands she acknowledge what she wants, what she knows, and what she intends. There's nowhere to hide — no plausible deniability, no strategic helplessness. This also means that she is ultimately responsible for her life, for the choices she makes, and for how her life turns out. She chooses to stand alone and there is nobody but herself to blame.

In spite of resistance to change and insisting on perfection, no one moves through life untouched. The attempt to remain untransformed by experience doesn't prevent the experiences themselves; it only prevents their integration. The refusal to be marked by life creates a paradoxical shallowness — an inability to develop the depth that comes only through surrender to transformation. Existing on surfaces is moving, charming, endearing and beautiful in younger women; in fully adult women, however, it is not only grotesque from an external point of view, but it also leaves a woman in a regressed state. She never truly witnesses her own depths, her own creativity, her own capacity to be vast, great and all-encompassing. She feeds off her past self rather than off life — she haunts the riverbanks of her own life, neither fully dead nor fully alive.

Actualised, she is capable of holding every experience without ever being reduced to any — she is always greater, always vaster. The experience integrated adds to the complexity, subtlety and nuance of a woman’s being, until, she, ideally, becomes the chalice that holds the entire human experience within herself.

Instead of aiming for perfection what you should aim for is the wholeness. The journey from perfection to wholeness is a descent — for a woman, this is a courageous plummet into the body's wisdom. Wholeness does not reject any aspect of life — wounds, scars, pain and everything else we may conceptualise as negative, are as much as parts of life as are the experiences that we may conceptualise as pleasant.

The deepest beauty of the Feminine comes not from its flawlessness but from its capacity to hold the wine of spirit without shattering. When a woman discovers that her experiences are not evidence of her unworthiness but the very portals through which the transformative spirit enters, she stops fleeing from life and begins at last to live it.

If you feel called to wholeness, today, I shall give a few techniques that you can adopt that can take you there.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Volupta to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.